Caught in the Perfectionism-Procrastination loop?

Is perfectionism driving you to procrastinate? It may seem counterintuitive, but a fear of failure can stand in the way of you achieving your goals. Read on to learn more…

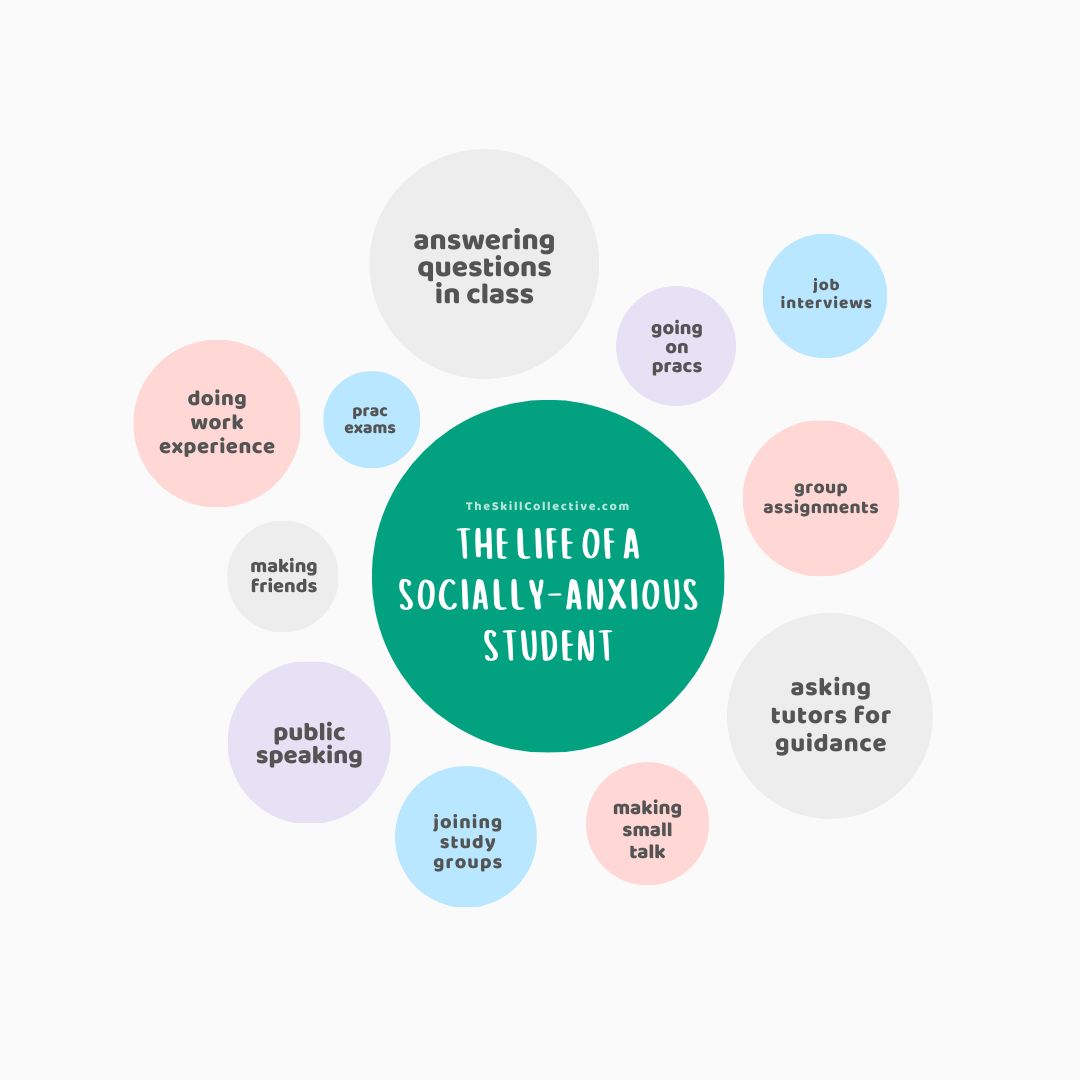

The Life of a Socially-Anxious Student

Living with social anxiety as a student can be challenging - speaking up in class, group assignments, public speaking, gaining work experience, making friends … the list of social situations is endless. But there’s no need to suffer further…read on to find how to go from surviving to thriving in your studies.