Caught in the Perfectionism-Procrastination Loop?

By Olivia Kingsley

Perfectionism is often viewed as a positive quality – after all, who wouldn’t want to be perfect? High achievers meet their goals, and this can lead to feeling accomplished. However, the dark side of perfectionism, Clinical Perfectionism, can actually harm our wellbeing, mental health, and performance. Clinical Perfectionism involves placing immense pressure on ourselves to meet extremely high (and often unattainable) standards [1], relentlessly striving for these standards, and basing our self-esteem based on the ability to achieve these standards[2]. When we (inevitably) fall short of meeting these standards, we experience negative emotions and low self-worth. Rather than helping us attain excellence, Clinical Perfectionism can actually result in a number of self-defeating behaviours, including procrastination [3]. Let’s look at Mia’s situation:

Mia, 22, is a university student who takes her studies very seriously and wants to impress her professors. She holds very high standards for her academic performance and believes that any grade lower than a high distinction is unacceptable. If she receives a grade she considers too low, Mia believes she is a failure and assumes that her professors are disappointed in her. Because of the immense pressure she faces, Mia delays starting assignments because she is terrified of making a mistake when writing the ‘perfect’ paper. This means that Mia starts her assignments at the last minute, which leaves her feeling rushed, guilty, and overwhelmed.

In Mia’s situation, procrastination has nothing to do with being lazy. Rather, her procrastination is directly tied to her fear of not attaining perfection. If this sounds familiar, here are some other signs that perfectionism could be driving procrastination [3]:

The thought of starting a project or assignment is too terrifying because it won’t be good enough.

Excessive amounts of time are spent in the planning phase (the ‘grand vision’), but doing the actual task is put off until the last minute because the output may fall short of the vision.

Actions are heavily driven by emotions, for example avoiding finishing a task until it feels “ just right”, or not starting an assignment because we’re “not in the right frame of mind”.

Easier, less intimidating (and less ego-threatening) tasks are prioritised, taking time away from those tasks that need to be completed.

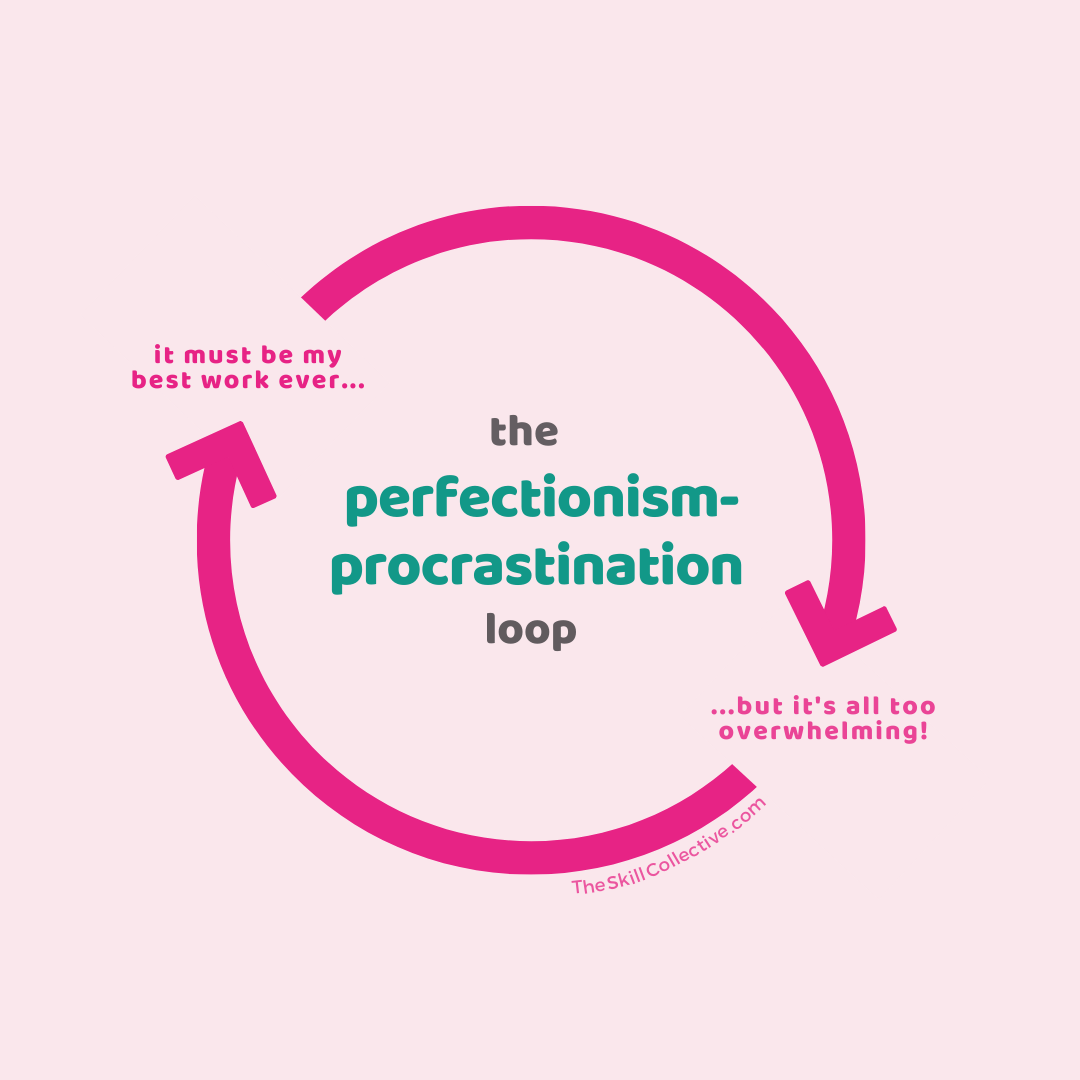

The challenge, though, is that while procrastination brings short-term relief, it’s later replaced by increased time pressure, feeling even more overwhelmed, and underperformance in general.

what maintains the perfectionism-procrastination loop?

How is this unhelpful perfectionism-procrastination loop maintained? Let’s look to those thoughts, feelings, and behaviours that keep us stuck in this loop.

The way we think

The way perfectionists think can really maintain clinical perfectionism and contribute to procrastination.[3][4]

Perfectionists are often hypervigilant for signs that their performance is not up to scratch. They may be sensitive to signs of negative feedback, or even tune in to their own stress and discomfort when attempting to start a task (and rationalising that this discomfort reflects a lack of ability).

Perfectionists can fall into the trap of unhelpful thinking styles. These thinking styles are often inaccurate but are accepted as reflecting reality. They unhelpful thinking styles serve to increase stress and overwhelm, which can be demotivating. Procrastination is a natural consequence when facing such negative emotions. These kinds of thinking styles include:

All or Nothing Thinking: This particularly relates to the attainment of unrealistically high standards, “If I don’t receive 100% on my test then I am a bad student”. Certainly, attaining these unrealistically high standards is unlikely, thus this way of thinking sets the perfectionist up to experience stress and overwhelm.

Catastrophic Thinking: This involves assuming that one will not be able to cope with negative outcomes, and that even a small mistake will be a disaster. “My reputation would never recover if I said the wrong thing at a work meeting”. When the consequences are blown out of proportion, is it any wonder that procrastinating on taking action seems to be the safer option?

Mind Reading: This involves predicting what other people are thinking, often making assumptions that they are judging you negatively, “My supervisor is so critical and exacting that they will rip my assignment to shreds and think I am utterly incompetent.” This type of thinking can then lead to procrastination when submitting work to be evaluated.

Misguided attributions and rationalisations following the outcome subsequently serve to reinforce the perfectionism-procrastination loop, for example believing that:

Attributing deadline-driven productivity to capability, “I do my best work under pressure!”. In reality, the work is done only because of the imminent deadline. The rest of the time

Rationalising outcomes as an underestimate of true abilities, thus preserving self-esteem, “Wow, look at that mark. Pretty remarkable given I didn’t have much time to do it. Imagine if I actually focused I could’ve done so much better!”

The way we feel

Since perfectionists tend to be highly self-critical, they experience negative emotions when their expectations are (inevitably) not met. The thinking styles described earlier keep perfectionists feeling bad about themselves and reinforce their low self-worth. When a perfectionist is unable to meet their high standards, they may experience feelings of anxiety, overwhelm, guilt, depression, and doubt.

These feelings may be so intense and unbearable that procrastination seems to be the safest and most comfortable option. [4]

The way we behave

Finally, behaviour plays a big role in maintaining the perfectionism underpinning procrastination. In the article Anxiety on Campus: What Students Need to Know about Managing Anxiety, our Fight or Flight response kicks in when we face a threat (as is the case of a task we see as challenging and demanding perfection). Procrastination is an excellent example of the Flight response, where we seek to avoid the threat of failure and the resulting negative feelings triggered by the task. Some common examples of procrastination behaviours include:

Avoiding making a decision: This may include being unable to choose an assignment topic because you need to pick the “perfect” one that will result in you making the most compelling presentation in order to earn top marks, or even putting off making a decision (in case it’s the incorrect one!) so that you just have to make do with whatever is left over.

Giving up too soon: It is common for perfectionists to give up trying because doing so means facing the possibility of failure. It feels more secure and safe to avoid the scrutiny.

Delaying starting a task: This can include avoiding starting assignments, or even spending an excessive amount of time on researching but not actually starting the assignment (but still feeling productive). Not committing means not having to deal with a less-than-perfect attempt.

All these procrastinating behaviours are problematic in that they not only increase psychological distress, but also maintain perfectionism. When we engage in procrastination behaviours, we never really learn if we are actually good enough, and our thoughts keep us stuck in the perfectionism-procrastination loop:

If we performed well, we can only imagine how much better we could’ve done if only we’d started earlier and given ourselves a proper chance to shine (that is, our real potential hasn’t been fairly tested!)

If we perform poorly, then we can excuse it because of the pressure you were under (that is, our real potential was crushed under the weight of time pressure or anxiety).

Tips to break the perfectionism-procrastination loop

If you find yourself agreeing to all of the above, help is at hand. Here’s our tip sheet to help you break the perfectionism-procrastination loop [2] . As a sneak peek these include:

Count the costs of procrastination.

Set realistic and achievable goals .

Shift your mindset.

Shift your goalposts.

Show yourself compassion. .

Reach out and talk to a psychologist who works in the perfectionism-procrastination space (like us!).

A word of caution - the perfectionism-procrastination loop often reflects an entrenched pattern of thinking and behaving, accompanied by strong emotions. Progress will take time, and there will be setbacks along the way, so it’s best to adopt the approach of chipping away at it gradually.

REFERENCES

[1] Flett, G.L., Hewitt, P.L., Blankstein, K. R. & Koledin, S. (1991). Dimensions of perfectionism and irrational Thinking. Journal of Rational Emotive and Cognitive-Behavior Therapy, 9, 185-201.

[2] Baldwin, M. W., & Sinclair, L. (1996). Self-esteem and "if…then" contingencies of interpersonal acceptance. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 71, 1130 - 1141. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.71.6.1130

[3] Antony, M. M., & Swinson, R. P. (1998). When perfect isn't good enough: Strategies for coping with perfectionism. New Harbinger Publications.

[4] Fursland, A., Raykos, B. and Steele, A. (2009). Perfectionism in Perspective. Perth, Western Australia: Centre for Clinical Interventions

[5] Egan, S.J., Wade, T.D., Shafran, R., & Antony, M.M. (2014). Cognitive-behavioral treatment of perfectionism. New York: The Guilford Press.

(Updated July 2023) Experiencing stress and burnout? The stressors of modern day and lifestyle challenges may be making things worse. Here’s what to do about it.